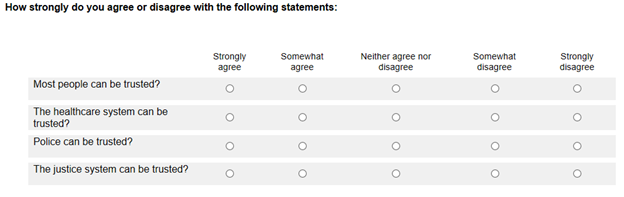

For bipolar scales, avoid scale labels that contain more options for one side (usually positive) because it biases the responses towards that side for the following reasons:

- The lack of sufficient negative options leads the respondent to believe a negative response is discouraged (i.e. social desirability).

- Respondents might incorrectly assume that the scale points represent the true distribution of the population and try to agree with the majority.

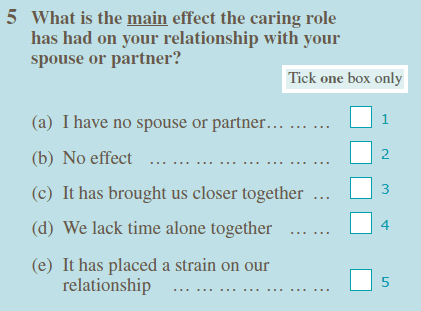

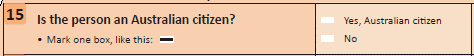

Include an appropriate neutral option to give respondents a formal way to indicate when (they think) a question does not apply to them. (See 'Include explicit 'Don't know', 'Not applicable' or 'Refusal' response options where valid' in the 'Question structure' chapter).

Avoid forcing respondents to produce an opinion on the spot as this often results in answers that are neither accurate nor stable.

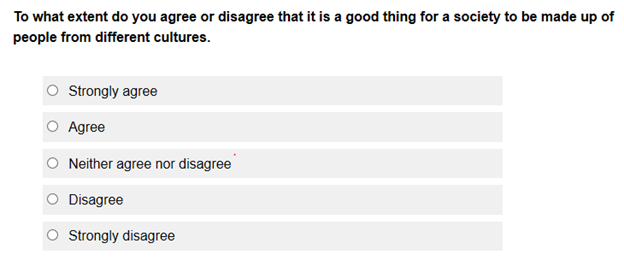

A neutral option can be placed in the middle of a bipolar scale (e.g. Neither agree or disagree in Diagram 26).

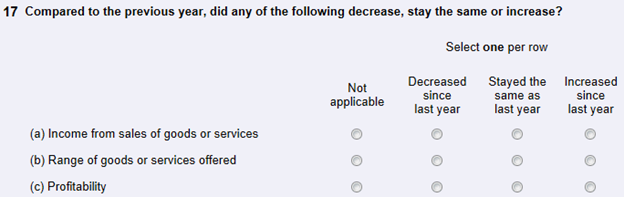

Consider the following guidelines for presenting neutral options in a self-administered mode:

- Place the 'Don't know' and 'Not applicable' options at the end of the scale to ensure that respondents consider all the preceding response options first.

- Avoid placing the 'Don't know' and 'Not applicable' options in the middle of the scale. There is a tendency for respondents to select a response from the mid-point (i.e. central tendency) regardless of the label which creates bias.

Neutral options can be presented in the following ways when using an interviewer-administered mode:

- The 'don't know', 'not applicable' or 'refusal' options are not read out but used when respondents genuinely cannot answer the question.

- The 'don't know', 'not applicable' or 'refusal' options can be read aloud in some cases. For example, under a proxy reporting arrangement, it might be common for the selected person to genuinely not know information about, or attitudes of, another person in the household.

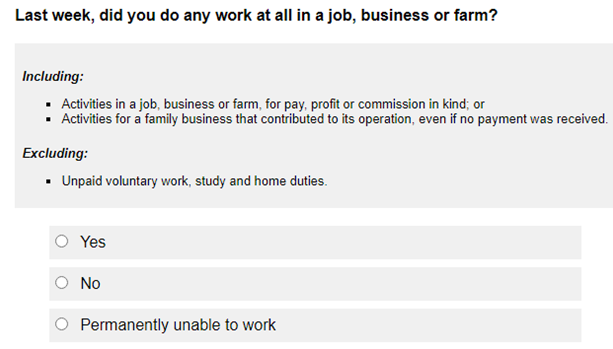

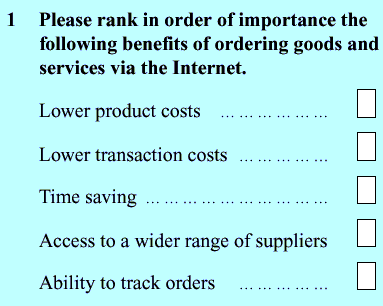

Consider the following factors when determining the number of scale points to be used

- The labels chosen

- The topic being measured

- The extent or level of intensity required

- Whether a middle or neutral option is to be included (e.g. neither satisfied nor dissatisfied)

- If a 'Don't know' or 'Not applicable' option is necessary

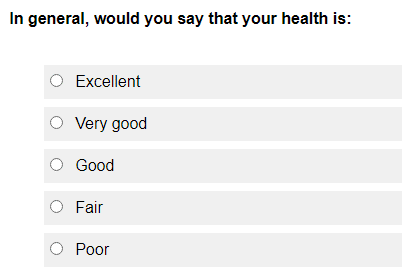

Use a five-point rating scale for non-factual questions when a survey is visually presented to respondents (e.g. web form and paper form).

Avoid using scales that have more than five points in telephone surveys. Respondents must listen and remember all the information about the question, including the rating scale, without visual aids during a telephone survey. Consequently, complex scales can contribute to cognitive burden for respondents.

Ensure that a five-point bipolar scale consists of the following:

- One high intensity option for each direction (e.g. 'very dissatisfied' and 'very satisfied)

- One mid-range intensity option for each direction (e.g. 'dissatisfied' and 'satisfied')

- One neutral option (e.g. 'neither satisfied nor dissatisfied')

Multiple-item scales use more than one question to measure the same topic of interest (e.g. attitudes) in a more reliable and valid way. They are preferred for non-factual questions over a single question because:

- the respondent's answer cannot be verified as there are usually no 'right' or 'wrong' answers

- non-factual topics (e.g. attitudes) can be quite complex and it is unlikely that a single question will reflect them adequately

- they improve consistency of a measure such that the same results are obtained when the measure is used repeatedly (i.e. reliability)

- they reduce instability related to the actual question form and wording, context, and mood at a particular point in time.

Use suitable existing validated scales known for obtaining reliable data where possible for non-factual questions.

For less important non-factual topics, a single question can be used, however it will be less reliable and more likely to be subjected to bias.