General forms design principles: Question structure

Introduction

The way questions are asked influences how well a survey works.

When designing or developing any survey, it is important to conduct testing with actual respondents to find out whether the questions can be understood and answered accurately. Following the guidelines alone cannot ensure that questions will work as intended by the researcher.

Refer to the Language chapter when designing or developing survey questions.

Follow basic guidelines for designing questions

Consider the following factors when you design questions

- The data needs of users

- The level of accuracy needed

- Whether data is available from the respondent

- Whether the language used is appropriate for respondents

- The data item definitions, standard question wordings and any other relevant information (e.g. accounting standards, or classifications)

- The office processing system you are using, including editors, data entry staff, OCR etc.

- The sequencing, or order of questions

- The answer space required for each question.

A question in a survey is any set of words which ask the respondent to give information. For example, 'Have you ever served in the Australian Defence Force?' (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1

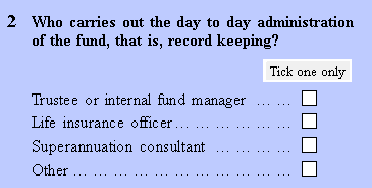

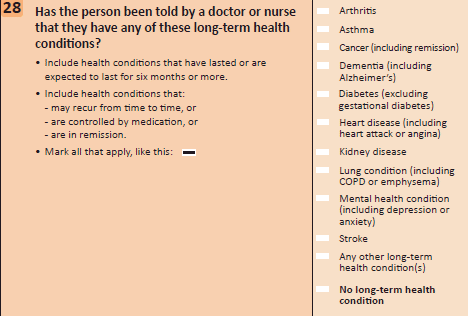

A question can have subsidiary questions, often called 'sub-questions'. Sub-questions are additional questions that help to answer your main question (Diagram 2).

Diagram 2

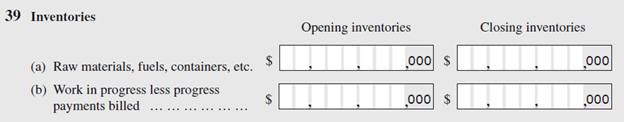

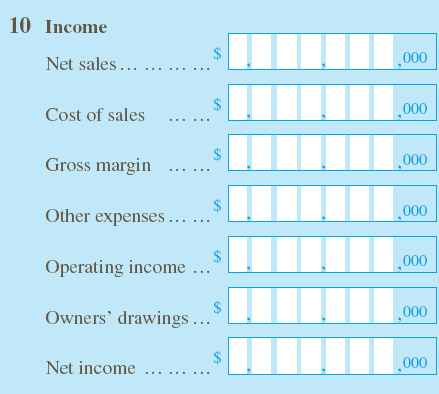

For financial data items in business survey forms, use captions or items based on accounting standards which are well understood by respondents. A question consisting of a caption or item only, does not use a question mark or any other punctuation such as a full stop (Diagram 3).

Diagram 3

Avoid joining separate concepts together in a question. These double-barrelled questions are characterised by using the conjunctions 'and' and 'or'.

Double barrelled questions are cognitively difficult to answer because only some of the concepts may apply to the respondent, or all may apply but in opposite directions. Respondents are therefore more likely to make mistakes when answering these questions or skip over them altogether. An example of a double barrelled question is: How often and for how long do you visit the gym per week?

Keep questions as simple as possible. Do this by placing the broadest or most common category first and using specialised or less common categories as examples.

For example, do ask:

- 'Does this business use the services of a financial advisor, such as an accountant or a tax advisor?'

Don't ask:

- 'Does this business use the services of a financial advisor or accountant or tax advisor?'

Avoid qualifiers in a question if they contain a lot of information. This can:

- make a familiar concept seem unfamiliar

- interfere with the respondent's grasp of the main element of a question.

Alternative ways of presenting the information from qualifiers include:

- turning qualifiers into instructions (Diagram 4).

Diagram 4

- placing the information from short qualifiers to the end of a question in brackets (Diagram 5).

Diagram 5

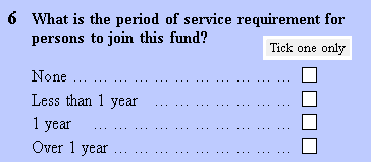

Choose a set of simple questions over one complex question (Diagram 6).

Diagram 6

Use exact or precise terms for the concept and context being measured. For example, avoid using a general term like 'screen time' if you are only interested in time spent watching TV shows and not time spent playing games.

Avoid using the following when writing a question

- ambiguous or vague words (e.g. 'frequently' or 'average' can mean different things to different respondents)

- acronyms

- abbreviations

- jargon

Use simple words.

Avoid double negatives because they make questions difficult to interpret.

Ask questions in a balanced way

Phrase rating questions in a balanced way where both the negative and positive options are presented (e.g. "Do you favour or oppose....").

Balanced questions imply that responses in either direction are acceptable and therefore minimises bias.

Consider the following when writing the negative and positive options:

- List the negative option first, especially for sensitive questions, to indicate that it is a perfectly acceptable response (also see 'Carefully consider where sensitive questions are placed').

- Choose words for the negative and positive options that are exact opposites (e.g. 'Difficult' and 'Easy').

- Ensure that the negative and positive options are equivalent in intensity (e.g. 'Very difficult' and 'Very easy').

Avoid leading questions

Leading questions steer respondents towards a particular answer or make some responses seem more desirable than others.

For example, asking: 'Do you believe that climate change will impact your holding?', is leading because it assumes the respondent agrees the climate is changing.

The same question could be rephrased to avoid leading respondents towards a particular answer, e.g. 'Do you consider the climate affecting your holding has changed?'

Avoid loaded questions

Avoid loaded questions. Loaded questions contain words or phrases that bring to mind powerful emotions or opinions.

For example, don't ask: 'Do you engage in behaviour that puts your health at risk such as smoking?' The phrase 'puts your health at risk' is loaded because it is likely to provoke strong emotions or opinions. Respondents will tend to react more to the loaded phrase than the issue posed in the question.

Instead, ask the question in a more neutral way, e.g. 'Do you currently smoke?'

Use examples

Including examples is important because it can help:

- clarify the meaning of a question

- increase the level of detail reported

- reduce the level of inaccurate responses by helping people remember information that they would not have otherwise recalled (also see 'Be aware of memory bias.').

Consider the following guidelines when determining the type and number of examples that are provided in questions:

- Include both common (e.g. eating carrots) and unusual (e.g. eating celeriac) examples. This will aid recall of common as well as more infrequent or unusual events.

- Keep the list of examples short. Longer lists may be incorrectly interpreted by the respondent as an exhaustive list from which to choose an answer.

- Test questions to help identify those that require examples to help clarify their meaning and determine the number of examples required.

Be aware of order effects

A list of response options can be ordered or unordered.

Ordered response options are arranged in a particular sequence.

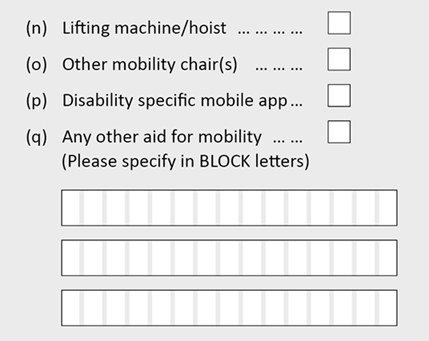

Ensure a list of options is ordered whenever there is an inherent order (Diagram 7).

Diagram 7

Unordered response options (Diagram 8) have no inherent order that offers a natural graduation of answers (also see 'Nominal categories' in the 'Question type' chapter).

Diagram 8

Be aware of order effects where the order in which the response options are presented influences the respondent's answer. For example, the respondent may interpret the options as having an order that was not intended. This perceived order could lead the respondent to misinterpret the question or give inconsistent answers.

Order effects are more pronounced in longer lists of unordered response options. For example, respondents might only select the first few options of a long list, so they don't have to read the others.

There are two common types of response order effects:

- Primacy effects mean that options presented earlier are more likely to be selected. These are prevalent in self-administered surveys.

- Recency effects mean that options heard last by the respondent are more likely to be selected. These tend to occur in interviewer-administered surveys.

Use a split sample experiment during the testing stage to assess whether response order effects are likely to be problematic.

Reducing the cognitive demands for respondents will help counter both order effects and also satisficing behaviour where respondents choose the first adequate response option rather than carefully considering each one.

Consider the following solutions if pre-testing shows that response order effects are likely to be an issue:

- Keep the question wording simple.

- Ensure the survey is as short as possible.

- Place the most common answer first (which also reduces the reading that respondents must do).

- List the options randomly for web forms or computer-assisted interviewing instruments.

- Counterbalance the order in which response alternatives are presented by giving a random half of respondents one order, and the other half the reverse order if using a paper form.

- For multi-modal surveys, use the same method to manage order effects across modes (e.g. counterbalancing for both web and paper form).

- Use two orders for rating scales (i.e. negative to positive or positive to negative).

- Include no more than ten options on the list if the items contain two or three words.

- Aim to have a maximum of five options if each item is longer than two or three words.

- Ensure that all response options are as grammatically similar as possible (e.g. how it is phrased, the length of the items).

- Categorise response options into groups or sub-questions.

Be aware of context effects

The order in which questions are placed can produce context effects. When preceding questions influence the response to later questions it can lead to bias and error.

Consider these opposite approaches to manage context effects depending on why general questions are included:

- Use the 'funnel principle' by placing general questions first followed by detailed and specific questions. General questions are more susceptible to influence from more detailed and specific questions than vice versa.

- Use a 'specific-first order' by placing questions covering specific topics before the more general question (e.g. providing a breakdown of income before providing 'total income' or an 'overall satisfaction' rating at the end of a list of contributing aspects). Ordering questions in this way 'creates' a controlled context effect where respondents are encouraged to consider specific topics before answering a more general question.

- This helps to reduce both bias and the diversity of interpretation.

Use classifications for factual questions

Use classifications for factual questions (see 'Factual questions' in the 'Question type' chapter).

Formal classification systems attempt to describe something which is almost infinitely varied in structured categories (e.g. Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classifications (ANZSIC)).

There are two key challenges related to using formal classification systems:

- It can be difficult to ensure a consistent understanding of the classification categories, particularly the residual (i.e. "other") categories, as the full range of things these categories include may not be clear.

- The formal classification may not correspond to the informal classification systems respondents use.

Be prepared to adapt formal classifications to get useful answers from respondents.

Consult organisations responsible for statistical standards for guidance. The Australian Bureau of Statistics standards and classifications should be used where applicable.

Use testing

Use testing to find out how well:

- respondents understand the categories used in the classification

- the categories apply to respondents' circumstances

- interviewers can code the responses.

For paper forms, investigate the following solutions in the order listed if testing shows that respondents might find it hard to use the classification:

- Maintain the conceptual basis of the classification categories but change the examples of the categories to suit the population of the survey.

- Use specifically designed response categories and map these to the output classification after the data has been collected.

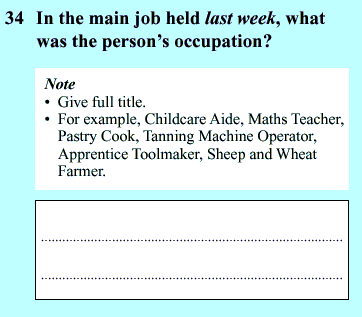

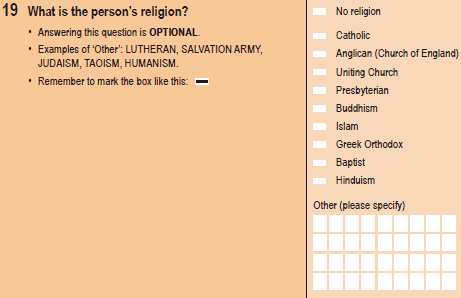

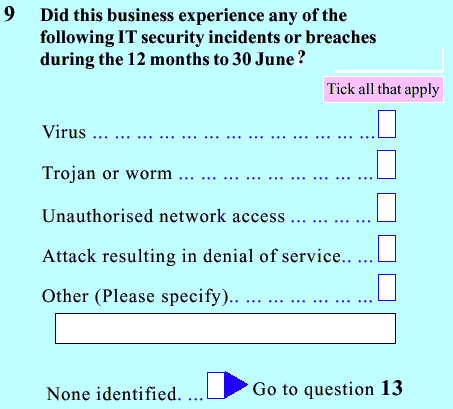

- Include a partially-closed question in the classification to give respondents (or the interviewer) the opportunity to provide different responses (Diagram 9).

Diagram 9

Use open-ended questions only and interpret the responses according to the formal classification system (Diagram 10).

Diagram 10

Consider using an open-ended question with a coder for web forms or a computer-assisted interviewing instrument. A trigram coder, for example, dynamically codes the open text response. The user (either the respondent or interviewer) types in the first three letters of the response, then selects the correct option from a list that pops up in a separate window.

Test all the alternatives before deciding on the best method for your survey.

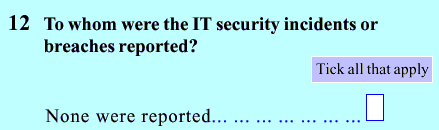

Include explicit 'Don't know, 'Not applicable' or 'Refusal' response options where valid

For multi-modal surveys, ensure that 'don't know' and 'not applicable' options offered to respondents are equivalent across modes. For example, if a 'don't know' option is offered in the self-administered mode (e.g. web form), consider whether the same option should be explicitly offered in the interviewer-administered version.

Self-administered surveys

Be clear about what you want respondents to do when questions do not apply to them or if they don't know the answer to the question.

Consider the following options that eliminate the need for a 'not applicable' response option:

- Instruct respondents to leave answer boxes blank when they have no response or data to enter. This option is suitable for surveys that contain mostly factual questions and when sparse data is expected. For example, for some business surveys, respondents may not have data to enter for a large portion of the questions so instructing them to leave the boxes blank creates a better user experience.

- Use a filter or sequencing question to instruct respondents to skip past questions that are not applicable to them or that they do not have an answer to.

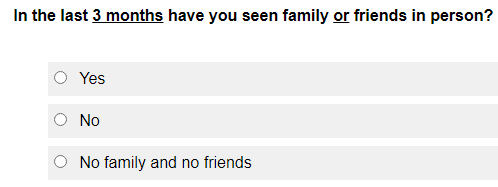

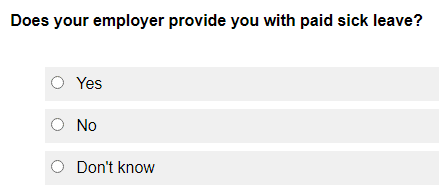

Avoid other types of questions that allow respondents to correctly leave the answer space blank when they have been sequenced to that question. These questions make it unclear whether the respondent should have recorded an answer or not. Include a 'not applicable’ or 'don't know' response option to allow respondents to indicate they do not think the question applies to them or that they have no knowledge of that topic (Diagram 11 and Diagram 12).

Diagram 11

Diagram 12

Placing the 'not applicable' option at the top of the response options list (Diagram 13) is appropriate when:

- it is a factual question

- respondents are likely to be confident in their answer

- acquiescence (i.e. where respondents tend to simply agree to everything) is not expected

- reading through the entire list of response options creates unnecessary respondent burden

- it is needed to act as a filter question because there is a lack of space on paper forms for a separate filter question.

Diagram 13

Placing the 'not applicable' option at the end of the response options list (Diagram 14) is appropriate when:

- acquiescence is anticipated

- misinterpretation of the question scope or other confusion is expected

- it is important to encourage respondents to consider the entire list of response options.

Diagram 14

Make 'don't know' and 'not applicable' options visually distinct, if possible (e.g. different colour, a vertical line separating this option, use bold) (Diagram 14).

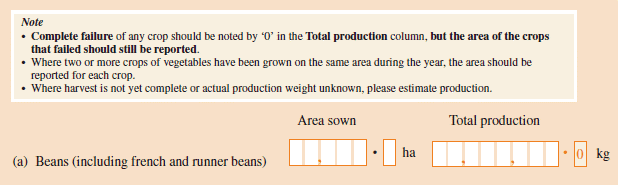

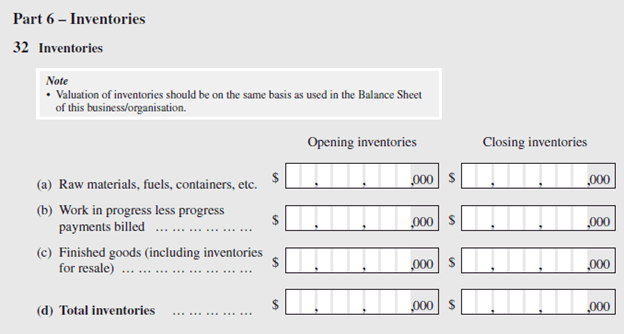

Instruct respondents to record zero when they need to indicate a particular result (Diagram 15) or demonstrate that they have read a particular question when sequencing errors are anticipated.

Diagram 15

Interviewer-administered surveys

Include non-substantive response options (e.g. 'Don't know', 'Not applicable, 'Refusal') for interviewers to use when respondents:

- indicate that they don't know the answer

- indicate that the question is not applicable to them

- refuse to answer the question

- are reporting as a proxy on behalf of another household member.

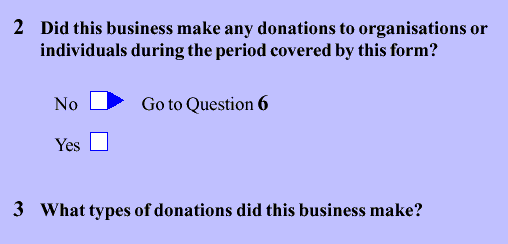

Use filter or sequencing questions to guide respondents

A filter or sequencing question asks respondents to make a choice, where one answer leads them to the next question, and the other to a different question or place on the form.

Use a filter or sequencing question to help the respondent understand the sequence of questions and skip past questions that are not relevant to them (Diagram 16).

Diagram 16

Place the sequenced response first in filter questions. This takes the respondent to a subsequent question without having to read the other option.

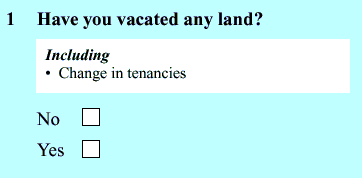

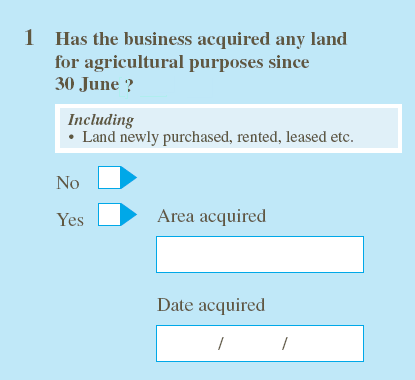

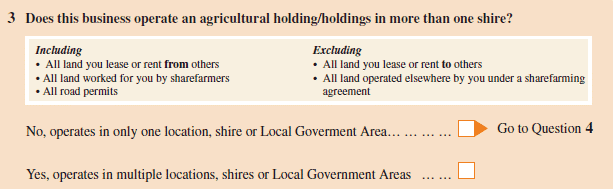

Ensure respondents are given enough information to select the applicable response option in a filter question by providing instructions (e.g. definitions, 'Including', 'Excluding') and clearly wording the response options (Diagram 17).

Diagram 17

Include a 'none of the above' option at the end of the response options with the sequencing instruction where it is appropriate (Diagram 18).

Diagram 18

Avoid using filter questions towards the end of the survey. Respondents' motivation to provide optimal responses may wane as they progress through the survey. Consequently, they may select a response that helps them avoid answering further questions.

Avoid strongly worded filter questions. For example, 'Have you read enough about [topic] to have an opinion?' as opposed to 'Do you have an opinion on [topic] or not?'.

Strongly worded filter questions may discourage respondents from expressing their opinion (e.g. selecting a 'no' response) because it suggests a high level of knowledge is needed to answer the question. This may intimidate respondents who feel that they might not be able to adequately justify their opinions.

Do not use filter questions for sensitive topics because they discourage reporting (also see 'Carefully consider where sensitive questions are placed.'). Respondents may avoid options that project a socially undesirable image of themselves. This is more likely to occur in interviewer-administered than self-administered surveys.

Choose filter questions over conditional questions. For example, don't ask: 'If this business has a parent company, what is its name?' With a conditional question it is unclear whether a blank answer is a non-response or if the question has been correctly interpreted by the respondent.

Use computer-assisted or web surveys with automatic sequencing when there is a large amount of complex sequencing to avoid errors.

Be aware of memory bias

Answers to factual questions can be biased and subject to error because respondents may:

- 'remember' what should have been done rather than what was done

- recall salient events more accurately and over longer periods, including events that are of importance or interest to them, and events that happen infrequently.

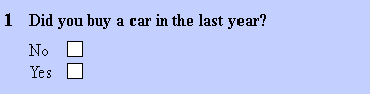

Respondents may also report that an activity happened during the reference period when it actually occurred before or after the reference period (called telescoping). For example, data from the question in Diagram 19 may be inflated by those who bought a car 13 months ago or more.

Diagram 19

Consider the following approaches to aid recall and enhance accurate reporting:

- Ask questions that relate to some form of record keeping (e.g. 'Did you buy a car in [YYYY]'? or 'Did you buy a car in the period of 1 January to 31 December [YYYY]?').

- Make the reference period as short as possible. Respondents are more likely to remember their activities in the last month than in the last year.

- Conduct testing to ensure that respondents can recall the information for the specified period.

- Break a question down into several simple questions (Diagram 20).

Diagram 20

- Group questions dealing with the same topic together (also see 'Group questions by topic.').

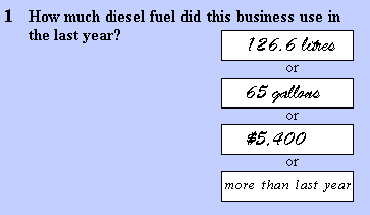

- Allow respondents to report in the unit they are most familiar with or that is most accessible to them where appropriate (Diagram 21).

Diagram 21

For interviewer-administered surveys, respondents may feel they need to answer a question quickly to avoid long pauses. Help respondents recall information to facilitate more accurate reporting:

- Train interviewers to read the questions more slowly to promote respondent deliberation as respondents may model their behaviour on that of the interviewer.

- Encourage respondents to take their time searching their memory (i.e. not saying the first thing that comes to mind).

Place questions in a sensible and logical order

Start with simple questions to establish and later maintain respondents' motivation to complete the survey. Respondents or interviewers will generally work through the questions in the order they appear.

Use the order of questions to facilitate a conversation, between the form and the respondent. The respondent must be able to easily understand and follow the flow of the conversation.

Help respondents navigate their way through a self-administered paper form:

- Only include 'go to' instructions when respondents should skip questions, or where it is unclear which question, they should answer next. Without this instruction, respondents will generally answer questions sequentially

- Ensure sequencing instructions are clear and obvious so respondents can follow them and get to the question that is relevant to them.

Use matrices sparingly as respondents:

- Cannot follow an obvious single path when responding and this increases their cognitive burden

- May overlook information that is not presented in a sequential format

- Could take longer to process information and are more likely to make errors when conceptually related information is presented separately in the row and column headings.

Be aware that in an interview, respondents may answer an early question and provide answers to a topic covered later in the survey, disrupting the flow of the survey. Help interviewers maintain the flow of the conversation:

- Have them explain the order of upcoming questions as part of their script to make respondents aware that they have an opportunity to provide their answers at a later stage

- Provide further guidance through their training and briefing.

Group questions by topic

Group questions about related topics together and present questions in a meaningful order. This is especially important for self-administered surveys because when respondents are confused, they may:

- read the next question when they are not sure what the current questions means

- review the previous question and the answer provided

- scan the local topic context when they are not sure about the relevance of the current question topic.

Ask all questions relating to a particular topic before going on to the next one. This enhances both the comprehension and the recall of the respondent (see 'Be aware of memory bias.').

Keep context effects in mind (see 'Be aware of context effects.').

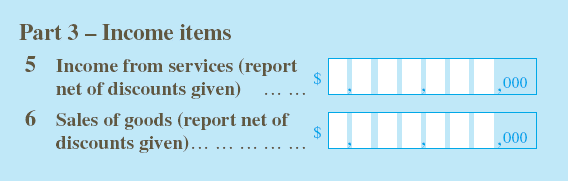

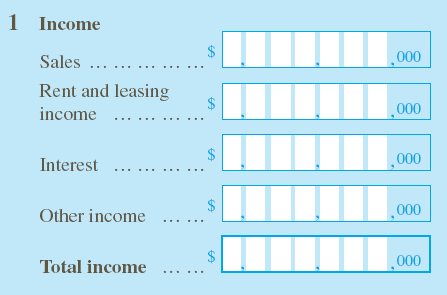

Group questions in a way that aligns with the concepts commonly understood by a particular cohort of respondents. For example, group questions related to income generated by a business together (Diagram 22).

Diagram 22

Use sections or parts

Make the survey easier to complete by using sections or parts:

- Respondents may need to skip some parts and return to complete them later (e.g. some information may not be available at the time).

- Several different people may need to enter data into the one form (e.g. accounts staff, HR staff).

Ensure the questions within the part or section are more related to each other than they are to the questions in the surrounding groups.

Ensure section and part headings are not merely replicating question text as this increases clutter without aiding comprehension.

Label the part or section with letters (e.g. Part A - General information, Part B - Employment) or numbers (e.g. Part 1 - General information, Part 2 - Income).

Avoid using sections or parts when it is not necessary because it makes the form visually complicated.

Avoid having a section or part with only one question if possible.

Ensure parts or sections are used consistently throughout the form and that every question belongs to one. Inconsistent use will make it difficult for the respondent to tell which questions go together, and what the questions mean.

Apply the following guidelines to paper forms that have parts or sections:

- Start a new section or part on a new page. This helps respondents realise that the topic has changed.

- Repeat part headings with '-continued' on even-numbered pages (i.e. 'left' pages) where a part continues over to the following page (also see the 'Typography' chapter for paper forms).

- Do not repeat the part heading on odd-numbered ('right' pages), as the facing page already displays the part heading.

- Continued part headings can be repeated on odd-numbered pages if desired, provided that this be done consistently throughout the form, and does not further clutter a page already full of question content.

Use sections or parts to help interviewers navigate through the questions they are asking more easily. However, interviewers should not read out the section title. If respondents need to be informed about a new section or part, interviewers will be given a script for a transition statement that is phrased in a conversational tone. For example, 'I would now like you to think about the visa you had when you first came to live in Australia. We will call this your first visa.'

Carefully consider where sensitive questions are placed

Be aware that when respondents are required to answer questions using information (e.g. health or income details) that might seem socially undesirable, they may provide a response that they believe is more 'acceptable'. This tends to be more of an issue for interviewer-administered surveys compared to self-administered surveys.

Avoid placing sensitive questions at the beginning of the form. This may contribute to non-response if respondents are unwilling to continue with the survey. Respondents will be more comfortable answering sensitive questions as they progress and build rapport with the survey or interviewer.

Avoid placing sensitive questions all together at the end of the form if this results in unrelated topics being mixed. This can be confusing and can also highlight to the respondent that the questions are supposed to be sensitive.

Place sensitive questions in a section of the form where they are most meaningful in the context of other questions. For example, in an Income question from an unincorporated business, the item 'owners’ drawings' might be sensitive. Putting it in the context of this question may make it less sensitive (Diagram 23).

Diagram 23

Place less desirable options first when a sensitive question has several response options. This indicates to respondents that it is acceptable for them to choose from all the options, even the less desirable one (Diagram 24).

Diagram 24

Keep 'No/Yes' or 'Yes/No' options in the same order

Arrange 'No/Yes' or 'Yes/No' options in the same order throughout the form, regardless of which order you choose.

Place the least desirable answer first for 'No/Yes' (or 'Yes/No') options to counter the tendency to report socially desirable behaviour. This helps indicate that the less desirable answer is an acceptable response.

Adopt a 'No/Yes' order to help prevent acquiescence. For example, when questions are not particularly sensitive, respondents may just say 'yes' to all the questions whether it is indeed the case or not.

Format questions consistently

Present the main question text on the same line as the question number with the answer box to the right or below it.

Include 'sub questions' if there is a strong association between the parts or if the main question is a filter to the next main question.

Label the sub-parts of a question whenever they are long or have their own instructions. This makes it clear which bits belong together.

Ensure that any sub-sub parts are quite short and simple. Otherwise, the whole question gets too complicated, and the sub-question should be turned into a main question.

Follow the pattern 1 a, b, c, 2 a, and so on for labelling questions and sub questions.

Ensure that each labelled question has its own answer box (Diagram 25).

Do not use decimals to label questions and sub-questions (e.g. 1, 1.1, 1.2).

Diagram 25

Additional resources

Barnett, Robert (1991) "Empirical bases for documentation quality", Proceedings from the first conference on quality in documentation, Centre for Professional Writing, University of Waterloo, 57-92.

Frohlich, David (1986) "On the organisation of form-filling behaviour", Information Design Journal, 5/1, 43-59.

Flynn, James (1996) "Constructing and reconstructing respondent attitudes during a telephone survey", Proceedings of the section on survey research methods, American Statistical Association, 895-899.

Jenkins, Cleo R., & Dillman, Don A. (1997) "Towards a theory of self-administered questionnaire design" Survey Measurement and Process Quality, Lyberg et al (eds), John Wiley & Sons, 165-195.

Krosnick, J.A. & Presser, S. (2010). Question and questionnaire design. In P.V. Marsden & Wright, J.D. (Eds.) Handbook of Survey Research (2nd Edition). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Oppenheim, A.N. (1992). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement (new edition). London: Continuum.

Schuman, Howard, & Presser, Stanley (1981) Questions and Answers in attitude surveys: Experiments on Question Form, Wording and Context, Academic Press Inc., Orlando.

Schwarz, Norbert, & Hippler, Hans-Jurgen, (1991) "Response alternatives: the impact of their choice and presentation order", Measurement Errors in Surveys, Biemer, Groves, Lyberg, Mathiowetz & Sudman (eds), John Wiley and Sons, 41-56.

Schwarz, Norbert, Hippler, Hans-Jurgen, & Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth (1992) "A cognitive model of response-order effects in survey measurement", Context effects in social and psychological research, Schwarz & Sudman (eds), Springer-Verlag, 187-201.

Tourangeau, Roger, & Smith, Tom W. (1996) "Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context", Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 60: 275-304.