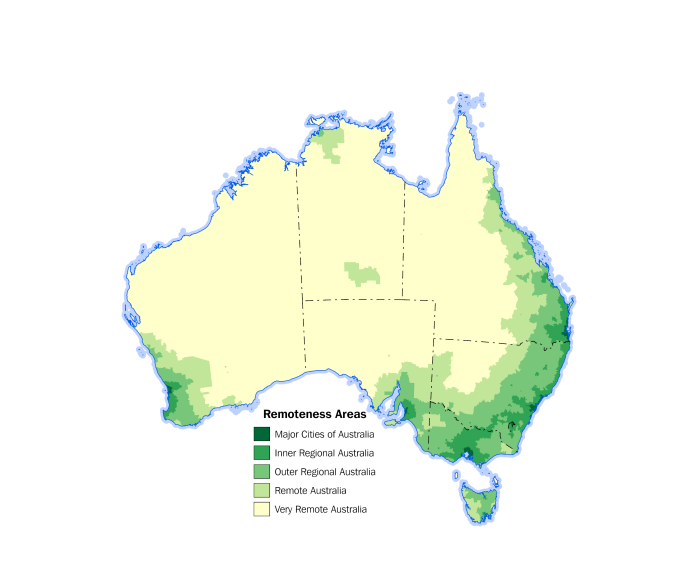

The following article presents National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Measures Survey (NATSIHMS) 2022–24 results for people living in Very Remote Australia.

This release has been developed in consultation with the ABS’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Surveys Advisory Group, a group of external stakeholders who have guided the content and release of data from this survey.

Any reference to persons/people/peoples in this product refers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons/people/peoples.

The ABS recommends that users refer to the NATSIHMS 2022–24 methodology for important information that will help with interpreting these statistics. This includes information on response rates, coverage and sample bias. Undercoverage is higher in the NATSIHMS 2022–24 compared to other ABS surveys and caution is recommended when using these estimates.