Part B - Economic flows

3.6.

Economic flows are defined in paragraph 3.4 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as the creation, transformation, exchange, transfer, or extinction of economic value. They involve changes in the volume, composition, or value of a unit’s assets, liabilities and net worth. A flow can consist of a single event, such as the receipt of a tax payment from a taxpayer, or can relate to the cumulative value of a set of events over the accounting period, such as the continuous accrual of interest expense on a government bond.

3.7.

There are two types of economic flows recognised in the GFS system. These are known as:

- transactions; and

- other economic flows.

Transactions

3.8.

A transaction is defined in paragraph 3.5 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as an economic flow that is an interaction between institutional units by mutual agreement or through the operation of the law, or an action within an institutional unit that is analytically useful to treat like a transaction, often because the unit is operating in two different capacities. In this context, mutual agreement is intended to mean that there was prior knowledge of the flow and consent given by each unit to enter into the transaction, but does not necessarily mean that the units entered into the transaction voluntarily.

3.9.

Paragraph 3.5 of the IMF GFSM 2014 also states that some transactions (such as the payment of taxes) are enforced by law. Despite their compulsory nature, tax payments are regarded as mutually agreed interactions between the government and taxpayers, and are therefore treated as transactions. This is because there is collective recognition and acceptance by the community of the legal obligation to pay taxes. Similarly, the actions necessary to comply with judicial or administrative decisions may not be undertaken voluntarily, but because they are taken with prior knowledge and consent of the parties involved, these too are considered transactions in GFS.

3.10.

The GFS system also recognises as transactions, certain flows that occur within in-scope units where a unit is viewed as operating simultaneously in two different economic capacities. Therefore, flows such as depreciation are recorded as transactions in GFS because the unit who owns the relevant asset is seen as simultaneously acting as both the owner of the depreciating asset and as the consumer of the service provided by the asset. Another example of an internal or intra-unit flow which is recognised as a transaction in GFS is the run-down of inventories in calculating non-employee expenses or use of goods and services.

3.11.

The types of unit interactions intended to be excluded from the definition of a transaction in GFS include events such as the illegal seizure or destruction of a unit's property by another unit.

3.12.

All transactions can be recorded as either exchanges or transfers in the GFS system.

Exchanges

3.13.

An exchange is defined in paragraph 3.9 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as a transaction where one unit provides a good, service, asset, or labour to a second unit and receives a good, service, asset or labour of the same value in return. Compensation of employees, purchases of goods and services, the incurrence of interest expenses, and the sale of an asset such as an office building are all considered to be exchanges in GFS.

3.14.

Exchange transactions do not include entitlements to collective services or benefits, which are considered to be transfers. This is because the amount of collective service or benefit that may eventually be receivable by an individual unit is not proportional to the amount payable. Taxes and non-life insurance claims are examples of such transactions classified as transfers due to the collective nature of the benefits.

Transfers

3.15.

A transfer is defined in paragraph 3.10 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as a transaction in which one institutional unit provides a good, service, or asset to another unit without receiving from the latter any good, service, or asset in return as a direct counterpart. This type of transaction is also referred to as being 'unrequited', or a 'something for nothing' transaction. Transfers can also arise where the value provided in return for an item is not economically significant or is much below its current market value. General government units engage in a large number of transfers which may be compulsory or voluntary in nature. Government grants, government subsidies, non-life insurance claims and taxes are all considered to be transfers in GFS.

3.16.

Paragraph 3.13 of the IMF GFSM 2014 states that taxes are treated as transfers in GFS, even though the units making these payments may receive some benefit from services provided by the government unit receiving the taxes. For example, in principle no one can be excluded from sharing in the benefits provided by collective services such as public safety. In addition, a taxpayer may even be able to consume certain individual services provided by government units. However, it is usually not possible to identify a direct link between the tax payments and the benefits received by individual units. Moreover, the value of the services received by a unit usually bears no relation to the amount of the taxes payable by the same unit.

3.17.

Paragraph 3.14 of the IMF GFSM 2014 also specifies that there is uncertainty if the contributing unit will receive any benefits and, if it does receive benefits, they may bear no relation to the amount of the premiums previously paid. Non-life insurance claims are also treated as transfers in GFS. This type of insurance entitles the units making the payment to benefits only if one of the events specified in the insurance contract occurs. That is, one unit pays a second unit for accepting the risk that a specified event may occur to the first unit. Non-life claims are considered transfers because in the nature of the insurance business, they distribute income between policyholders to those who claim, as opposed to all policyholders who contribute.

3.18.

In GFS, transfers may be either current or capital in nature.

Capital transfers

3.19.

Capital transfers are defined in paragraph 3.16 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as transfers in which the ownership of an asset (other than cash or inventories) changes from one party to another; or that oblige one or both parties to acquire or dispose of an asset (other than cash or inventories); or where a liability is forgiven by the creditor. Capital transfers are typically large and infrequent, but capital transfers cannot be defined in terms of size or frequency. Cash transfers involving disposals of non-cash assets (other than inventories) or acquisition of non-cash assets (other than inventories) are also considered to be capital transfers. A capital transfer results in a commensurate change in the stock position of assets of one or both parties to the transaction.

3.20.

A transfer in kind without a charge is a capital transfer when it consists of:

- the transfer of ownership of a non-financial asset (other than inventories);

- the forgiveness of a liability by a creditor when no corresponding value is received in return; and

- major non-recurrent payments in compensation for accumulated losses or extensive damages or serious injuries not covered by insurance policies.

3.21.

A transfer of cash is a capital transfer when it is linked to (or conditional on) the acquisition or disposal of a non-financial produced asset by one or both parties to the transaction.

Current transfers

3.22.

Current transfers are defined in paragraph 3.17 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as all transfers that are not capital transfers. Current transfers directly affect the level of disposable income and influence the consumption of goods or services. That is, current transfers reduce the income and consumption possibilities of the donor and increase the income and consumption possibilities of the recipient. For example, social benefits, subsidies and food aid are current transfers.

3.23.

Paragraph 3.18 of the IMF GFSM 2014 states that it is possible that some cash transfers may be regarded as capital transfers by one party to the transaction and as current transfers by the other party. In order to ensure that a donor and a recipient do not treat the same transaction differently, a cash transfer should be classified as capital for both parties even if it involves the acquisition or disposal of an asset, or assets, by only one of the parties. When there is doubt about whether a transfer should be treated as current or capital, it should be treated as a current transfer.

Combinations of exchanges and transfers

3.24.

Some transactions appear to be exchanges but are actually combinations of an exchange and transfer. Paragraph 3.11 of the IMF GFSM 2014 states that in such cases, a transaction should be partitioned (see explanation in paragraph 3.31 to 3.32 of this manual for the definition) and recorded as two separate transactions, one that is only an exchange and one that is only a transfer. An example of this type of transaction is where a general government unit sells an asset at a price that is clearly less than the market value of the asset, or at a price that is clearly above the market value of the asset. In this example, the transaction should be divided into an exchange at the asset's market value, and a transfer equal in value to the difference between the sale price and the market value.

Monetary and non-monetary transactions

3.25.

The GFS system also includes transactions in which the final consideration is cash (known in GFS as monetary transactions), as well as transactions in kind (known in GFS as non-monetary transactions).

Monetary transactions

3.26.

Monetary transactions are defined in paragraph 3.8 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as those in which one institutional unit makes a payment (or receives a payment), incurs a liability (or receives an asset), to (or from) another institutional unit stated in units of currency. In GFS, all flows are recorded in monetary terms, but the distinguishing feature of a monetary transaction is that the parties involved express their agreement in monetary terms. For example goods or services are usually purchased (or sold) at a given number of units of currency per unit of the good or service. All monetary transactions are interactions between two institutional units, recorded as either an exchange or a transfer (see paragraphs 3.15 to 3.18 of this manual for the definition).

Non-monetary transactions

3.27.

Non-monetary transactions are defined in paragraph 3.19 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as transactions that are not initially stated in units of currency. These include all transactions that do not involve any cash flows, such as barter, in kind transactions, and certain internal transactions. For GFS purposes these transactions must be assigned a monetary value because GFS records flows and stock positions expressed in monetary terms. The entries therefore represent values that are indirectly measured or otherwise estimated. The values assigned to non-monetary transactions have a different economic implication than do monetary payments of the same amount, as they are not freely disposable sums of money. Nevertheless, to have a comprehensive and integrated set of accounts, it is necessary to assign the best estimate of current market values to the items involved in non-monetary transactions.

3.28.

Paragraphs 3.21 to 3.25 of the IMF GFSM 2014 give the following examples of non-monetary transactions:

- Barter transactions - where two units exchange goods, services, or assets other than cash of equal value. For example, a government unit may agree to trade a parcel of land in an industrial area to a private corporation for a different parcel of land that the government will use as a national park, or between nations governments may trade strategic natural resources for another kind of product or service.

- Remuneration in kind - this occurs when an employee is compensated with goods, services, or assets other than money. Types of compensation that employers commonly provide without charge or at reduced prices to their employees may include meals and drinks, uniforms, housing services, transportation services, or child care services.

- Other payments in kind - these occur when payment is made in the form of goods and services rather than money. A payment to settle a liability can be made in the form of goods, services, or non-cash assets rather than money. For example, a government unit may agree to settle a claim for past-due taxes if the taxpayer transfers ownership of land or non-financial produced assets to the government.

- Transfers in kind - these may be used to increase efficiency, or to insure that the intended goods and services are consumed. For example, aid after a natural disaster may be more effective and be delivered faster if it is provided in the form of medicine, food, and shelter instead of money. Also, a general government unit might provide medical or educational services in kind to ensure that the need for those services is met.

Rearrangement of certain GFS transactions

3.29.

Some transactions are modified in macroeconomic statistics to properly reflect their underlying economic nature and substance more clearly. The following definitions and discussions regarding rerouting, partitioning and reassignment appear in paragraphs 3.28 to 3.30 in the IMF GFSM 2014, and have been reproduced below.

Rerouting

3.30.

Rerouting records a transaction as taking place through channels that differ from the actual ones, or as taking place in an economic sense when no actual transactions take place. Rerouting is often required when a unit that is in fact a party to a transaction does not appear in the actual accounting records because of administrative arrangements. Two kinds of rerouting often occur:

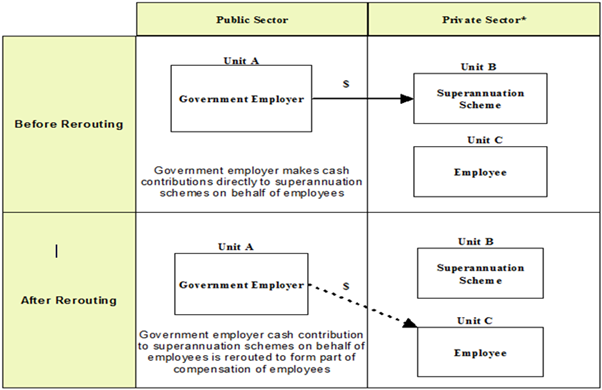

- In the first kind of rerouting, a direct transaction between unit A and unit C is recorded as taking place indirectly through a third unit B. For example, if government employees are enrolled in a superannuation scheme, accounting records may show the government unit making employer contributions directly to the superannuation scheme on behalf of its employees. However in macroeconomic statistics, these contributions are part of the compensation of employees and should be recorded as being paid to the employee. In such a case it is necessary to reroute the payments so that the government is seen as paying the employees, who then are deemed to make payments of the same amount to the superannuation scheme. As a result of the rerouting, these contributions are included as part of the employee expenses of government - see Diagram 3.1 below.

Diagram 3.1 - Rerouting of government employer contributions to superannuation schemes.

- In the second kind of rerouting, a transaction of one kind from unit A to unit B is recorded with a matching transaction of a different kind from unit B to unit A. For example, when a non-resident SPE of government borrows abroad, transactions should be imputed in the accounts of both the government and the non-resident SPE as if the SPE has extended a loan to government, and government has invested the corresponding amount in the SPE. This rearrangement of the transactions reflects government’s involvement in the non-resident SPE which would otherwise not be captured in government accounts.

Partitioning

3.31.

The IMF uses the term partitioning to refer to situations where a single transaction is recorded as two or more differently classified transactions. Partitioning may be required in cases where it is logical from an accounting perspective to collect data as a single transaction, but for GFS purposes the transaction must be split into two or more transactions to be correctly recorded for economic purposes.

3.32.

An example of where partitioning may be appropriate in GFS is when a general government unit acquires an asset at above or below its current market price. If the acquisition of the asset by government is part of a competitive process, then the asset can be said to have been acquired at the current market price and no partitioning is required. However, if the acquisition of the asset is a deliberate action by government (e.g. as part of a bailout operation) and there is clear evidence that the amount paid for the asset is above or below the market value of the asset, then the transaction is partitioned into an exchange transaction to record the market value of the asset, and a transfer transaction under assets acquired below market value (ETF 1152, TALC, COFOG-A, SDC) and the difference would be recorded as assets donated (ETF 1262, TALC, COFOG-A, SDC).

Reassignment

3.33.

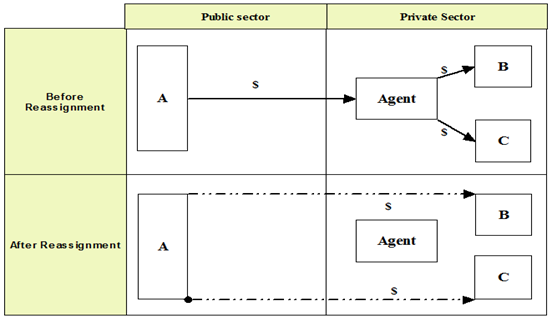

Reassignment records transactions arranged by third parties on behalf of others as taking place as if directly by the principal parties involved. Paragraph 3.30 of the IMF GFSM 2014 indicates that reassignment is required when one unit arranges for a transaction to be carried out between two other units, generally in return for a fee from one or both parties to the transaction. In this case, one unit acts as an agent for another unit. In GFS, the transaction must be recorded exclusively in the accounts of the two (or more) parties involved in the transaction and not in the accounts of the third party facilitating the transaction - see Diagram 3.2 below.

Diagram 3.2 - Reassignment of the transactions

Other economic flows

3.34.

In GFS, changes in the value of assets or liabilities that do not result from transactions are referred to as other economic flows. Other economic flows are flows that do not meet the definition of a transaction (see paragraph 3.8 to 3.12 of this manual for the definition). Paragraph 3.31 of the IMF GFSM 2014 describes other economic flows as those flows where the value of assets or liabilities change due to a naturally occurring event such as an earthquake, flood or fire. In these cases, the change in the value of the assets and / or liabilities need to be taken into account for GFS purposes even though they have not resulted from a transaction, and so they are recorded as other economic flows. Other economic flows are discussed in further detail in Chapter 11 of this manual.

3.35.

In GFS there are two major categories of other economic flows. These are described as holding gains and losses and other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities.

Holding gains and losses

3.36.

Holding gains or losses (which are also referred to as 'revaluations' in GFS) are defined in paragraph 3.33 of the IMF GFSM 2014 as changes in the monetary value of assets or liabilities resulting from changes in the level and structure of market prices, assuming that the asset or liability has not changed qualitatively or quantitatively. Holding gains or losses accrue purely as a result of holding an asset or liability over time, without transforming it in any way. Holding gains or losses can apply to any assets or liabilities held for any length of time during the accounting period. Any gains or losses made on the sale of assets are shown in output as holding gains or losses and not as GFS revenues.

3.37.

Holding gains and losses on assets and liabilities include changes resulting from exchange rate movements. The GFS basis for valuing stocks and flows is at their respective market values. Therefore in concept, holding gains and losses are continuously generated as market prices change with market activity, whether the holding gain or loss is realised or not. Holding gains or losses often occur on financial assets such as shares and securities that are traded on financial markets and are subject to exchange rate fluctuations.

3.38.

Further discussion on holding gains and losses may be found in Chapter 11 of this manual.

Other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities

3.39.

Economic flows that do not result from transactions or holding gains or losses are known as other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities (also sometimes referred to as 'other volume changes' in GFS). Other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities are events that bring about the addition of assets or liabilities to the GFS balance sheet or the removal (or part-removal) of assets or liabilities from the GFS balance sheet, and result in a change to GFS Net Worth.

3.40.

Economic flows due to other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities cover a wide variety of events. Paragraph 3.35 of the IMF GFSM 2014 lists the three most common categories of events that result in other changes in the volume of assets and liabilities. These are:

- Events that involve the appearance or disappearance of economic assets on the GFS balance sheet other than by transactions. In these cases, an other volume change is recorded when certain assets and liabilities enter and leave the GFS balance sheet through events other than by transactions. Examples include increases to the GFS Net Worth through mineral discoveries, or reductions in GFS Net Worth due to the unilateral writing off of bad debts by creditors.

- External events (exceptional and unexpected) that impact on the economic benefits derivable from assets and corresponding liabilities. Examples include the reduction of GFS Net Worth due to the destruction of assets by fire or some other catastrophe, or the depletion of natural assets (e.g. forests, fisheries) as a result of physical removal or use.

- Changes in classification. An example is when a change in the nature of the operations of a unit means it has to be transferred from General Government and reclassified as a Public Financial Corporation or a Public Non-Financial Corporation.

3.41.

Further discussion on other volume changes may be found in Chapter 11 of this manual.