Balancing item

A balancing item is an accounting construct obtained by subtracting the total value of the entries on one side of an account (resources or changes in liabilities) from the total value of the entries on the other side (uses or changes in assets). It cannot be measured independently of the entries in the accounts; as a derived entry, it reflects the application of the general accounting rules to the specific entries on the two sides of the account.

Capital expenditure

Capital expenditure is the amount spend on fixed assets like new buildings (such as hospitals) or medical equipment (such as CT scanners). It represents the cost of resources that last more than a year. This term applies to health expenditure reported under the System of Health Accounts.

Capital transfers

Transfers that are linked to the acquisition or disposal of an asset, either financial or nonfinancial.

Classification of Individual Consumption by Purpose

COICOP is the classification used to breakdown household final consumption expenditure by purpose or function.

Collective consumption

Collective consumption consists of the services provided simultaneously to all members of the community or to all members of a particular section of the community, such as all households living in a particular region. Collective services are automatically acquired and consumed by all members of the community, or group of households in question, without any action on their part. By their nature, collective services cannot be sold to individuals on the market, and are financed by government units out of taxation or other incomes. They are the public goods of economic theory (see individual consumption).

Consolidation

In the GFS system, consolidation is the process of eliminating intra-group flows and stocks that occur within a particular group of units, a sector or subsector. An institutional unit requires consolidation when the unit has multiple funds and accounts to carry out its operations, and there are flows and stock positions among those funds. Failure to eliminate intra-sectoral flows and stock positions results in aggregates that cannot measure interaction with outside units exclusively. It covers transactions undertaken within central government, the public non-financial corporations subsector, or within a state/territory government.

Consumption of fixed capital

The value of the reproducible fixed assets used up during a period of account as a result of normal wear and tear, foreseen obsolescence and the normal rate of accidental damage. Unforeseen obsolescence, major catastrophes and the depletion of natural resources are not taken into account. It is an SNA adjustment that replaces estimates of depreciation collected through business surveys and reported by government with modelled estimates.

Current prices

Estimates are valued at the prices of the period to which the observation relates. For example, estimates for 2002–03 are valued using 2002–03 prices. This contrasts to chain volume measures where the prices used in valuation refer to the prices of a previous period and to previous years' prices measures where the prices used in valuation refer to the prices of the previous period.

Current transfers

Current transfers consist of all transfers that are not transfers of capital. They include current transfers to nonprofit institutions and current transfers from the Commonwealth government to state and local government. These transfers involve one institutional unit providing a good, service or cash to another unit without receiving from the latter anything of economic value in return.

Current transfers from the Commonwealth government to state and local government

These transfers include financial assistance grants to the states and territories; grants to fund state and Territory health care services, education services, social security and welfare services, and similar specific grants for current purposes; special revenue assistance grants provided to certain states and territories; financial assistance grants for local governments which are provided through state and territory governments; and grants for current purposes made directly to local government bodies.

Current transfers to nonprofit institutions

Transfers for non-capital purposes to private non-profit institutions serving households such as hospitals, independent schools, and religious and charitable organisations.

Economically insignificant prices

A price is not economically significant when it has little or no influence on the amounts producers are willing to supply and the amount purchasers wish to buy. Economically insignificant prices may be charged in order to raise some token revenue and/or reduce (but not eliminate) excessive demand that may occur if goods and services are provided free of charge. An economically insignificant price may be set on administrative, social or political grounds for goods and services where the amount to be supplied is fixed.

Economically significant prices

Prices which have a significant influence on both the amounts producers are willing to supply and the amount purchasers wish to buy.

Exports of goods and services

The value of goods exported and amounts receivable from non-residents for the provision of services by residents.

Financial intermediation services indirectly measured

Banks and some other financial intermediaries provide services for which they do not charge explicitly, by paying or charging different rates of interest to borrowers and lenders (and to different categories of borrowers and lenders). For example, they may pay lower rates of interest than would otherwise be the case to those who lend them money and charge higher rates of interest to those who borrow from them. The resulting net receipts of interest are used to defray their expenses and provide an operating surplus. This scheme of interest rates avoids the need to charge their customers individually for services provided and leads to the pattern of interest rates observed in practice. In this situation, the national accounts must use an indirect measure of the value of the services for which the intermediaries do not charge explicitly. This measure is FISIM.

Whenever the production of output is recorded in the national accounts, the use of that output must be explicitly accounted for elsewhere in the accounts. Hence, FISIM must be recorded as being disposed of in one or more of the following ways: as intermediate consumption by enterprises; as final consumption by households or general government; or as exports to non-residents.

Government final consumption expenditure

Net expenditure on goods and services by public authorities, other than those classified as public corporations, which does not result in the creation of fixed assets or inventories or in the acquisition of land and existing buildings or second-hand assets. It comprises expenditure on compensation of employees (other than those charged to capital works, etc.), goods and services (other than fixed assets and inventories) and consumption of fixed capital. Expenditure on repair and maintenance of roads is included. Fees, etc., charged by general government bodies for goods sold and services rendered are offset against purchases. Net expenditure overseas by general government bodies and purchases from public corporations are included. Expenditure on defence assets is classified as gross fixed capital formation.

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic product is the total market value of goods and services produced in Australia within a given period after deducting the cost of goods and services used up in the process of production, but before deducting allowances for the consumption of fixed capital. Thus gross domestic product, as here defined, is 'at market prices'. It is equivalent to gross national expenditure plus exports of goods and services less imports of goods and services.

Gross fixed capital formation

Expenditure on new fixed assets plus net expenditure on second-hand fixed assets. This includes both additions and replacements.

Household final consumption expenditure

Net expenditure on goods and services by persons and expenditure of a current nature by private non-profit institutions serving households. This item excludes expenditures by unincorporated businesses and expenditures on assets by non-profit institutions (included in gross fixed capital formation). Also excluded are maintenance of dwellings (treated as intermediate expenses of private enterprises), but personal expenditure on motor vehicles and other durable goods and the imputed rent of owner-occupied dwellings are included. The value of 'backyard' production (including food produced and consumed on farms) is included in household final consumption expenditure and the payment of wages and salaries in kind (e.g. food and lodging supplied free to employees) is counted in both household income and household final consumption expenditure.

Imports of goods and services

The value of goods imported and amounts payable to non-residents for the provision of services to residents.

Individual consumption

Good or service that is acquired by a household and used to satisfy the needs and wants of members of that household. Individual goods and services can always be bought and sold on the market, although they may also be provided free, or at prices that are not economically significant, or as transfers in kind. Individual goods and services are essentially 'private', as distinct from 'public'.

Industry

An industry consists of a group of units engaged in the same, or similar kinds, of activity.

Input-output product classification

The IOPC is the detailed level product classification, organised according to the industry to which each product is primary. Input-output tables are compiled at this level of product classification.

Input-output tables

Input-output tables are a means of presenting a detailed analysis of the process of production and the use of goods and services (products) and the income generated in the production process; they can be either in the form of (a) supply and use tables or (b) symmetric input and output tables.

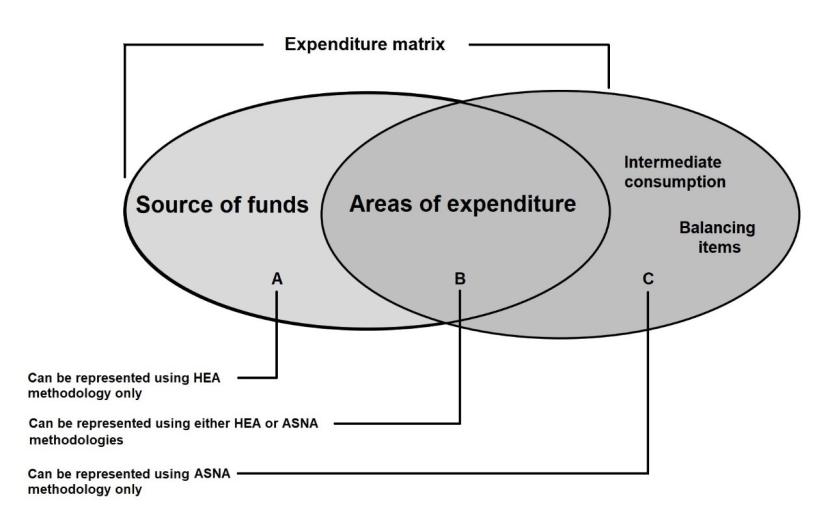

Intermediate consumption

Intermediate consumption consists of the value of the goods and services consumed as inputs by a process of production, excluding the consumption of fixed capital.

Net expenditure overseas

Net expenditure is an adjustment made to household spending so that total HFCE reflects the expenditure of resident households (in Australia and overseas) only. This adjustment is necessary because a number of the data sources for HFCE come from sales reported by Australian businesses. These sales include the expenditure by overseas visitors (treated as an export), and do not include expenditure of Australian overseas (recorded as an import). Expenditures by overseas visitors on fares, meals, accommodation, entertainment, recreation and other goods and services in Australia are deducted from the appropriate HFCE categories, while expenditures by Australian residents abroad are added.

Non-financial corporations

These units are corporations whose principal activity is the production of market goods or non-financial services. They include both private and public non-financial corporations.

Non-profit institutions

Non-profit institutions (NPIs) are legal or social entities created for the purpose of producing goods and services. Their status does not permit them to be a source of income, profit or other financial gain for the units that establish, control or finance them. In practice, their productive activities are bound to generate either surpluses or deficits but any surpluses they happen to make cannot be appropriated by other institutional units.

NPIs are classified to various sectors depending on the nature of the NPI. Market NPIs are allocated to either the financial corporations sector or non-financial corporations sector, depending on which sector they serve. Non-market NPIs that are controlled by government units are allocated to the general government sector. For example, an NPI which is mainly financed by government may be controlled by that government. It would not be considered controlled by government if the NPI remains able to determine its policy or programme to a significant extent.

Other non-market NPIs are not controlled by government. These units are private not-for-profit institutions serving households.

Not-for-profit institutions serving households

NPISHs provide goods and services to households free or at prices that are not economically significant. Most of these goods and services represent individual consumption but it is possible for NPISHs to provide collective services. There are two kinds of NPISHs:

organisations whose primary role is to serve their members, such as trade unions, professional or learned societies, consumers' associations, political parties, churches or religious societies, and social, cultural, recreational and sports clubs; and

philanthropic organisations, such as charities, relief and aid organisations financed by voluntary transfers in cash, or in kind, from other institutional units.

Over-the-counter medicines

Over-the-counter medicines are medicinal preparations that are not prescription medicines, and are primarily bought from pharmacies and supermarkets.

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

The PBS is a national, government-funded scheme that subsidises the cost of a wide variety of pharmaceutical drugs (see Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme).

Recurrent expenditure

Recurrent expenditure is generally on goods and services consumed within a year that does not result in creating or acquiring fixed assets. This term applies to health expenditure reported under the System of Health Accounts. Recurrent health spending includes: health goods (such as medications and health aids and appliances); health services (such as hospital, dental and medical services); public health activities; and other activities that support health systems (such as research and administration). Capital consumption or depreciation is included as part of recurrent spending.

Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

The RPBS provides assistance to eligible veterans (with recognised war or service related disabilities) and their dependants for pharmaceuticals listed on the PBS and a supplementary repatriation list, at the same cost as patients entitled to the concessional payment under the PBS (see Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme).

Social transfers in kind

Social transfers in kind consist of goods and services provided to households by government and NPISHs either free or at prices that are not economically significant.

Supply-use tables

Supply-use tables are matrices that record how supplies of different kinds of goods and services originate from domestic industries and imports, and how those supplies are allocated between various intermediate or final uses, including exports.

Transfers

Transfers may be either current or capital. See capital transfers and current transfers.