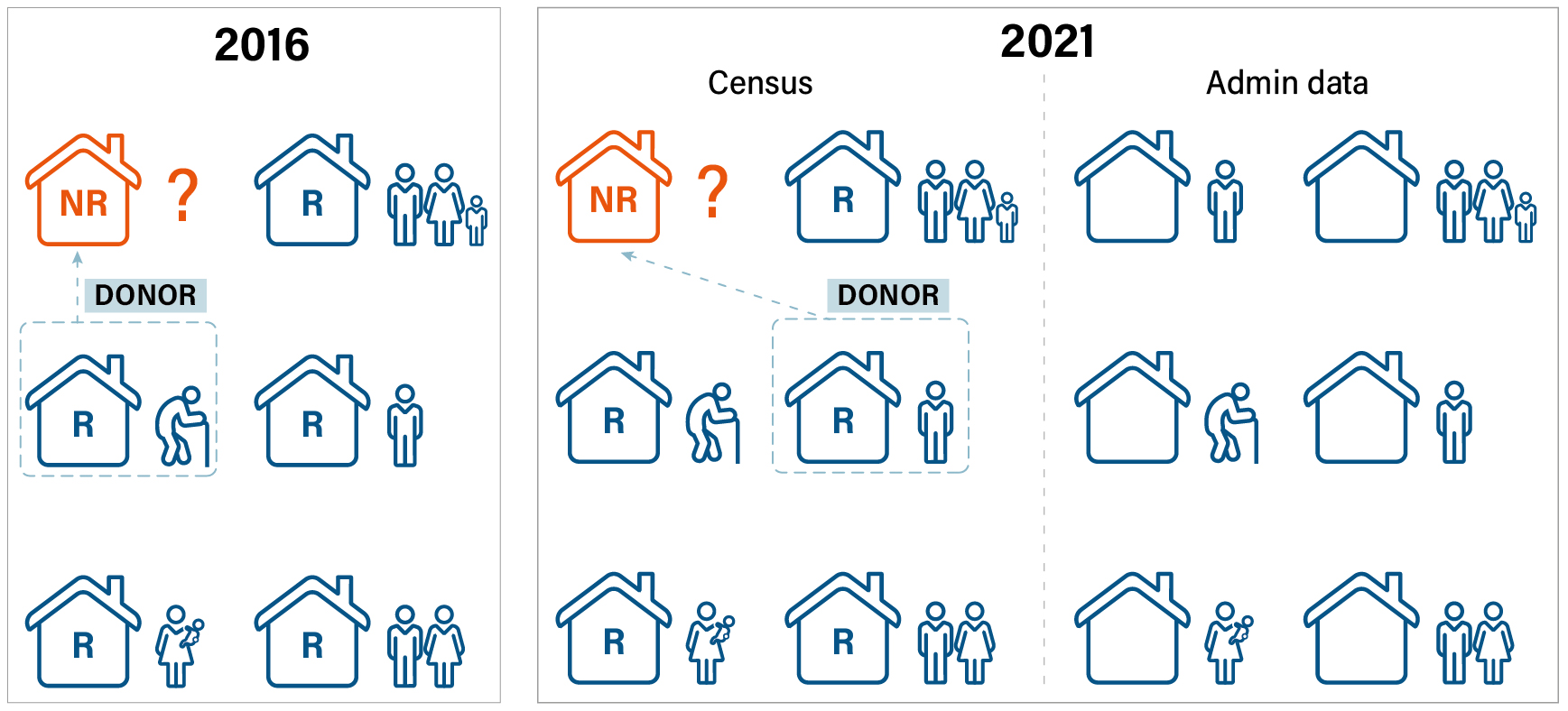

Historically, the occupancy of a dwelling in censuses was largely determined by field observation, including contact with the householder or neighbours. Occupancy was also determined when householders directly phoned the Census Contact Centre.

While occupancy rates in the 2016 Census were consistent with previous Censuses, the 2016 Post Enumeration Survey indicated that a proportion of dwellings were incorrectly deemed as occupied on Census night and therefore that the 2016 occupancy rates were over-stated. The 2016 Census Independent Assurance Panel highlighted the opportunity to improve the accuracy of occupancy determination.

New approaches implemented in the 2021 Census include:

- In 2021, householders could use the Census Digital Service to advise that a dwelling was unoccupied on Census night. There were two ways of doing this. First, through the online Census form in which householders who entered ‘0’ persons present were streamed out of the form to report the dwelling as unoccupied. This pathway was called the ‘zero stream’. A second method was to use a new self-service option on the Census website that allowed respondents to advise they were away on Census night.

- In addition, the 2021 Census used a probability model to create an indicator of occupancy. The model used administrative data and was applied to dwellings where insufficient information was obtained in the field to definitively determine if the dwelling was unoccupied. This process was applied as part of data processing.

More information about these approaches is published on the ABS website.[1]

[1] See Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020). Assessing administrative data to enhance the 2021 Census. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/research/assessing-administrative-data-quality-enhance-2021-census