Labour productivity measures the amount of output per hour worked. In the Australian economy over the past four decades, growth in labour productivity has been the predominant determinant of growth in real income per capita, a widely used measure of living standards¹. However, since 2012, growth in real compensation of employees has lagged behind labour productivity growth in the market sector².

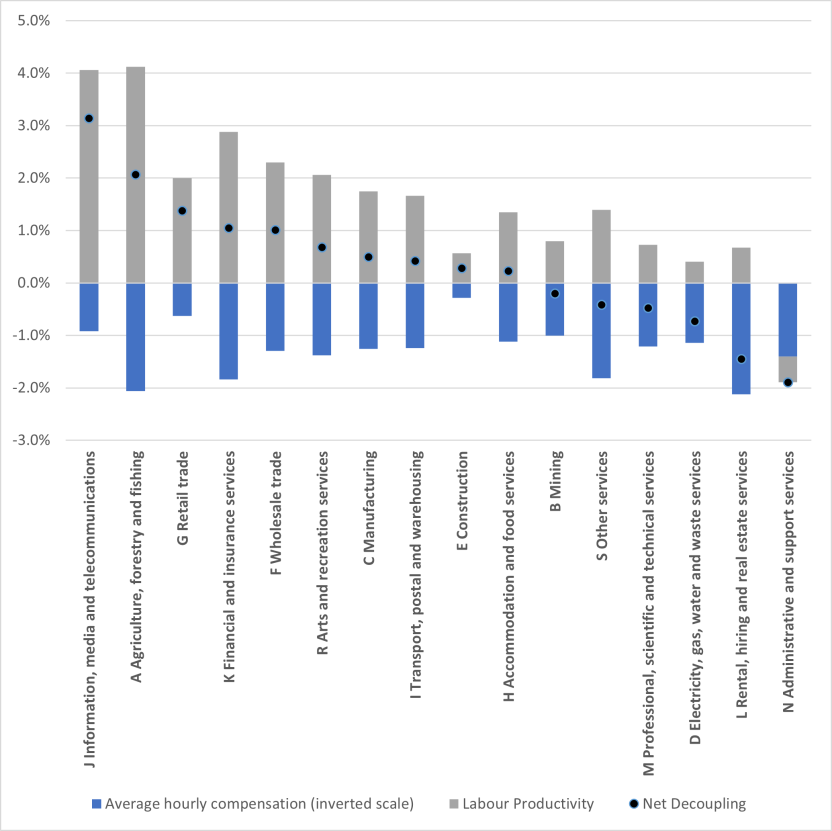

This article compares the growth in labour productivity and real hourly compensation for the market sector and selected industries since 1994-95. The article uses a decomposition framework to provide insights into the factors driving the difference between growth in labour productivity and worker compensation³.

On average, between 1994-95 and 2021-22, a 1.0 percentage point increase in labour productivity has resulted in around a 0.8 percentage point rise in real worker compensation for the market sector. In addition, industries with stronger productivity growth tended to have a greater disparity between growth in labour productivity and in real compensation.